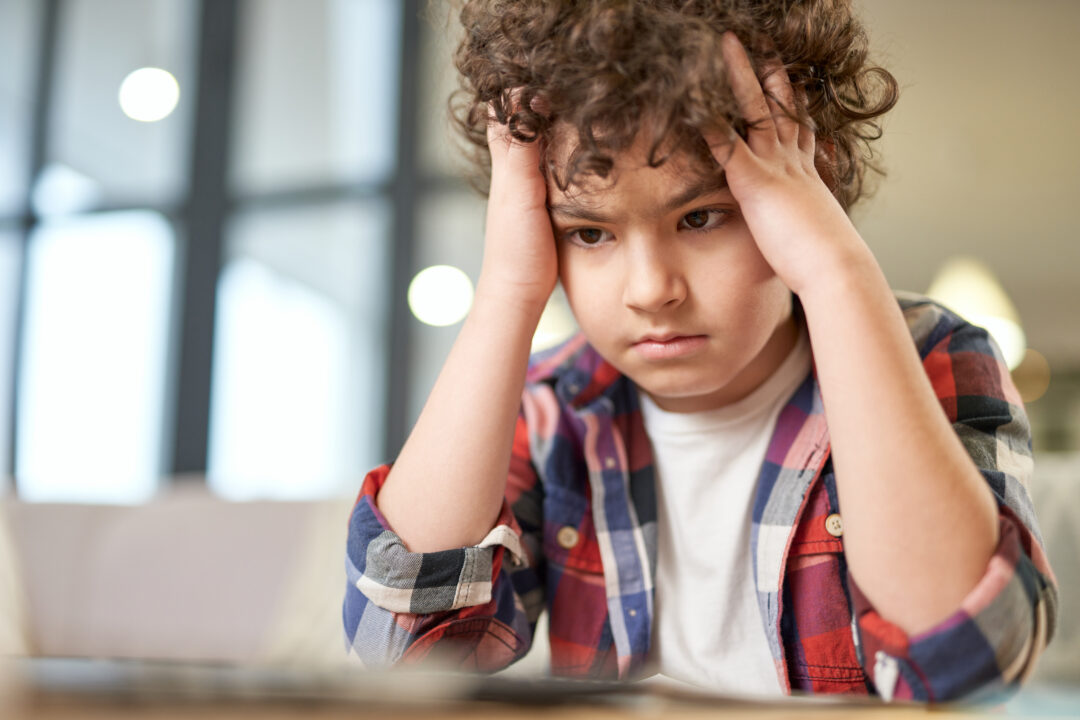

It is bound to happen. In a school, a daycare, a sports practice – maybe even in the middle of a religious service. A child – of any age – will misbehave, perhaps melt down, and even experience a crisis because, for any number of reasons, they cannot manage their overwhelming feelings. Their reactions in these moments can be intense, scary, aggressive, or destructive. Trauma-informed, resilience-focused adults can help support and regulate a child when this happens, using de-escalation and co-regulation tools and strategies. This is helpful for the child who is in crisis.

Other children and adults, however, often wonder, “What about the other kids?” This is a fair question that is prompted by additional concerns such as:

- Is it all right for children to witness others struggling? Will it traumatize them?

- Who will attend to and care for the children not currently in crisis?

- Why don’t children who act out and cause disruptions have more consequences?

- It isn’t fair that some children have more attention from the child-caring adult in charge than others.

Let’s look at how we might view these scenarios through the lens of the Circle of Courage resilience model. Throughout, the questions to the above frequently asked questions will be addressed.

Adults can prepare children in their care for these scenarios so everyone knows what they can expect—telling children what might happen, how the adult will respond, how the adult will prepare them for this kind of experience, and what will happen afterward.

Belonging.

All children need to feel a sense of connection and belonging – no matter what. It should not depend on their willingness or ability to be a particular person. Belonging isn’t a privilege but a fundamental human right (Shalaby, 2017). Children don’t get traumatized because they are hurt; they get traumatized because they are alone with that hurt (Mate, 2021).

A script for the adult:

Everyone struggles from time to time. Depending upon what is happening in your life or what has happened, along with your ability to cope, will depend on how you respond to certain situations. This does not make you bad or good – it just is. Chances are, we will experience someone in our group having a hard time – this could be a hard hour or even a hard day. I want you to know that if that happens, I will do what I can to help that person feel better. I will not be mad at that person, and they will not get in trouble. If they are struggling – it means that they need my help. I will ensure you all have a chance to learn and practice what you can do if something like this happens. When someone is struggling, things might get loud and unstructured, but I will do everything I can to keep all of us safe. I may be able to do that independently, or I might call another adult to help me. Later, when things settle down, we will always have an opportunity to talk together about what happened if you want to. We can do that as a group or individually. Even if one of us disrupts our room, everyone will always be welcomed back when calm and settled.

Mastery.

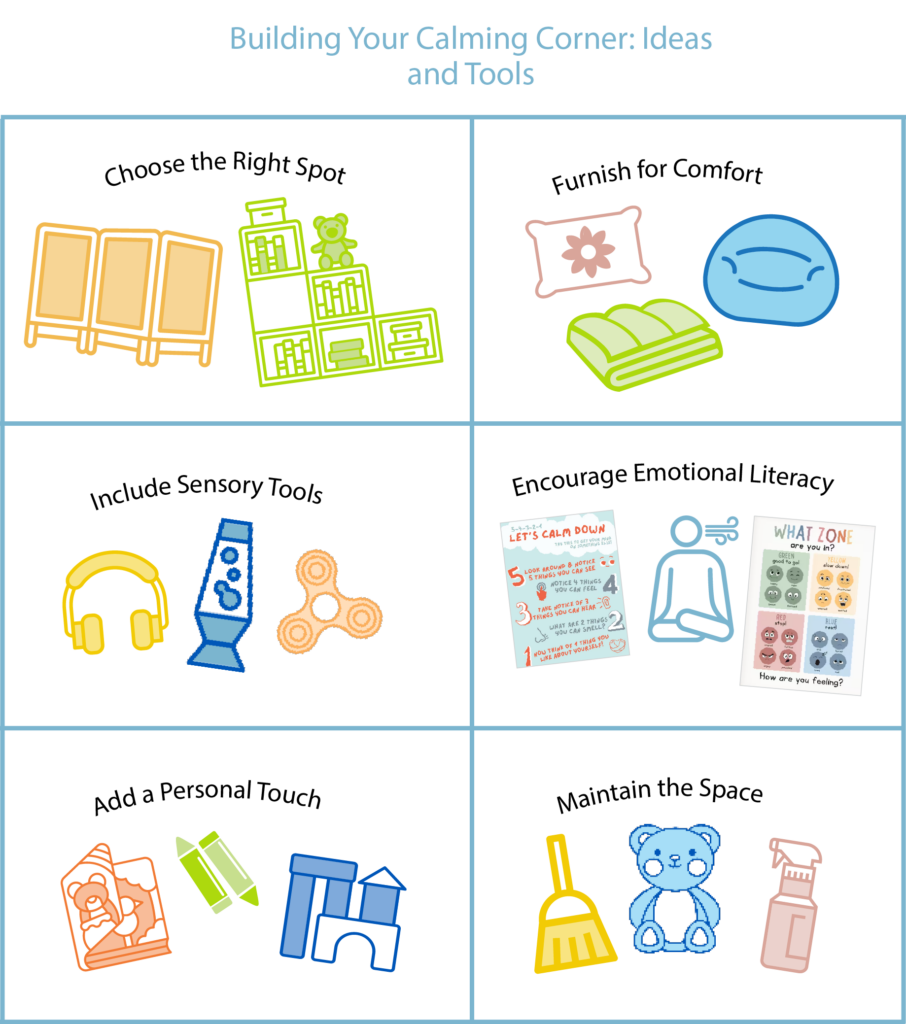

We cannot assume that all children have learned to regulate their emotions and behaviors. Children must have several opportunities to learn and practice emotional awareness and regulation. Just like learning to read and solve math problems, children must be taught skills and engage in experiences to try out what they have learned.

A script for the adult:

We will spend some time practicing techniques to help relax our bodies. We will practice different ways to slow down our breathing, close our eyes, imagine a happy memory, color designs, draw pictures, or write down our thoughts and feelings. All of us should practice how to calm ourselves down. I want you to feel good at calming yourself down, but I know this isn’t easy for everyone – it takes time and practice.

Independence.

Children feel safe when they know what to expect and when they are given choices about how to respond in potentially disruptive situations.

I want you to know that this room might not feel very calm if a child struggles. However, even if it is noisy or chaotic, please know I will take care of that. I will keep my voice even and stay in control. You can do what you need to do for yourself and others around you. Maybe you will try one of the relaxation techniques we practice. You may find that you want to go out into the hallway; you can do that; please stay close to the wall by our room. You may find that you want to put your head down on your desk, which is all right, too. Maybe you will want to sit with one of your friends. You have a choice about how best to take care of yourself.

I know it might not seem fair for those of you who are not disruptive and stay calm most of the time – you might think, why don’t you spend so much time with me, or why doesn’t that person get into more trouble? I understand why you may feel that way. Nevertheless, I have learned that what is fair is not always equal – some of us need more support than others. You know, I would need a lot of support picking apples from a tree because I am not very tall – I might need a stool (or a ladder), but someone else might be able to reach up and pick apples easily because of their height. Is it fair that I get a stool, but the other person does not? The other person does not need a stool, silly, but I do! So, this is the same as staying calm. Some of us find it more difficult than others, so some need more support. That is how it works – if someone needs something, we try to give it to them. As far as consequences are concerned, I think that if a person has a tough time, that is enough pain, and it does not do anyone any good to make them feel worse by punishing them on top of it. I will instead help teach them to better manage a situation next time with additional strategies and practice. I will support them.

Generosity.

We all have difficulty managing our emotions and behavior occasionally. This can be especially difficult when going through a particularly stressful time or have a history of very stressful experiences in our lives. We feel valuable when we can have empathy for and provide support to others.

A script for the adult:

Try to understand that the person struggling is not trying to be “bad,” but rather, they cannot manage their emotions and behavior and need help. You may find that you want to be with one of your friends and find a place in our room where you can sit together while I attend to the child who needs me, and if that is the case, please join your friend. If you are someone who feels good about your ability to calm yourself down and you find others having a hard time with what is happening in the room, please help your friends if they need support. I appreciate that we will all look out for one another.

There are no “other kids”; there are all kids. Providing unconditional connection and belonging, tools to help children manage their behavior and emotions, the agency to make choices when faced with difficult situations, and permission to use their value to support others can empower all children.

Download your free Mind Body Skills tool now!

References

Shalaby, C. (2017). Troublemakers lessons in freedom young children in school. New York, New Press.

Mate, G. (2021). The Wisdom of Trauma. Zaya Benazzo. Science and Nonduality.

Mackenzie Bentley, MA, LMFT, Director of Therapeutic Services at Starr Albion Prep; oversees the clinical treatment program of at risk youth ages 12-18 years of age. Mackenzie supervises master level licensed therapists who work with various populations through evidenced based practices.

Mackenzie Bentley, MA, LMFT, Director of Therapeutic Services at Starr Albion Prep; oversees the clinical treatment program of at risk youth ages 12-18 years of age. Mackenzie supervises master level licensed therapists who work with various populations through evidenced based practices. A Jackson, MI native, Heather Stiltner is a Licensed Professional Counselor in the State of Michigan, in addition to being a Nationally Certified Counselor and a Certified Trauma Focused Cognitive-Behavioral Therapist. She obtained her Bachelor of Arts degree from the Spring Arbor University, majoring Business Management. Her graduate work was completed at Siena Heights University in Organizational Leadership. Additionally, she obtained a second Master’s Degree at Spring Arbor University in Masters of Counseling.

A Jackson, MI native, Heather Stiltner is a Licensed Professional Counselor in the State of Michigan, in addition to being a Nationally Certified Counselor and a Certified Trauma Focused Cognitive-Behavioral Therapist. She obtained her Bachelor of Arts degree from the Spring Arbor University, majoring Business Management. Her graduate work was completed at Siena Heights University in Organizational Leadership. Additionally, she obtained a second Master’s Degree at Spring Arbor University in Masters of Counseling. Amy Swis is a licensed Clinical Social Worker as well as a Licensed Trauma Trainer. I have been working with children, adolescents, families, and the community at large for over thirty years. I have worked internationally as a Peace Corps Volunteer and domestically as a School Social Worker, Supports Coordinator, Disability Advocate, and Youth Worker. I have worked as a School Social Worker for Airport Community Schools, Dearborn Public Schools, and Detroit Public Schools. Currently, I am a School Social Worker at Lincoln Park Public Schools. A primary focus for Lincoln Park Public Schools is a Trauma Informed and Resiliency Focused approach with students and a Self Care component for staff. Building capacity within our practice and the district is a passion in order for staff and students to lead pro-active lives. This will empower neighborhoods and the communities we serve; more specifically for marginalized citizens.< ?p>

Amy Swis is a licensed Clinical Social Worker as well as a Licensed Trauma Trainer. I have been working with children, adolescents, families, and the community at large for over thirty years. I have worked internationally as a Peace Corps Volunteer and domestically as a School Social Worker, Supports Coordinator, Disability Advocate, and Youth Worker. I have worked as a School Social Worker for Airport Community Schools, Dearborn Public Schools, and Detroit Public Schools. Currently, I am a School Social Worker at Lincoln Park Public Schools. A primary focus for Lincoln Park Public Schools is a Trauma Informed and Resiliency Focused approach with students and a Self Care component for staff. Building capacity within our practice and the district is a passion in order for staff and students to lead pro-active lives. This will empower neighborhoods and the communities we serve; more specifically for marginalized citizens.< ?p>

Kim Wagner has been an occupational therapist for 26 years with 20 of them in the public school system. She also worked many years at sensory clinic and sensory camp. Kim has a master's degree in occupational therapy with a minor in early childhood development. She has also been certified in Infant Massage, Brain Gym, The Alert Self-Regulation Program, Trauma Informed Trainer (by STARR Global) and the Sensory Integration Praxis Test and Treatment. Kim currently works in Lincoln Park schools as an OT for the general education population. Kim is on the Behavior Support team and is part of the Trauma Informed Team. Kim's focus in her current position is providing regulation, sensory and trauma informed behavior support to students and teachers for a more successful educational experience.

Kim Wagner has been an occupational therapist for 26 years with 20 of them in the public school system. She also worked many years at sensory clinic and sensory camp. Kim has a master's degree in occupational therapy with a minor in early childhood development. She has also been certified in Infant Massage, Brain Gym, The Alert Self-Regulation Program, Trauma Informed Trainer (by STARR Global) and the Sensory Integration Praxis Test and Treatment. Kim currently works in Lincoln Park schools as an OT for the general education population. Kim is on the Behavior Support team and is part of the Trauma Informed Team. Kim's focus in her current position is providing regulation, sensory and trauma informed behavior support to students and teachers for a more successful educational experience.